You need to read Vol IV of the Machine Gun by Chinn.

Chinn’s series at Hyper books:

http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/MG/

This is not a simple question. Let me start off by saying that the cartridge case is the weakest link and has been the limiting factor in all action design. As Mike Walker's Rem M700 patent states:

BREECH CLOSING CONSTRUCTION FOR FIREARMS 2,585,195

Merle H. Walker, lion, N. Y., assignor to Rem ington Arms Company, Inc., Bridgeport, Conn., a corporation of Delaware Application

Prior art firearms of the type employing fixed metallic ammunition have always been dependent upon the metallic cartridge case for securing obturation with the Walls of the barrel chamber and preventing the rearward escape of gas from the barrel. As a result, the head of high intensity center-fire rifle cartridges has always been a massive chunk of brass of usually adequate strength to bridge over gaps between the end of the bolt and the chamber mouth, or clearance cuts for extractors, ejectors, and the like. However, in spite of this massive construction, the heads of cartridges, due to metallurgical deficiencies, barrel obstructions, or other difficulties, all too often fail in service, releasing white hot gas at pressures in excess of 50,000 pounds per square inch into the interior of the receiver. With some modern commercial and military rifles the effects of a burst head are disastrous, completely wrecking the action and seriously injuring or killing the shooter. One of the better known military rifles presents in alignment with the shooter's face a straight line passage down the left hand bolt lug guide groove, which, even though the receiver proper does not blow up, channels high pressure gas and fragments of the cartridge head into the location where they can do the most damage. It has been often, and truthfully, said that the Strength of most rifles is no greater than that of the head of the cartridges intended for use therein. The primary object of this invention is the provision of a firearm construction which is not thus dependent upon the strength of a cartridge head, ordinarily formed of a material of relatively low strength by comparison with the ferrous alloys used for the firearm structure.

This barrel comes from what is undoubtably the better known military rifle action mentioned in Mike's patent: the M1903. It is a poor action design, inferior in every aspect of departure from the M98 Mauser. A M1903 has the case head hanging out in a cone breech, absolutely no consideration for gas venting, and if the gas head ruptures, it blows gas directly into the shooters eye from a number of locations.

I have not uploaded even worse pictures of M1903 blowups. This one does have all the essential elements: the receiver ring blows, the stock split into pieces, because the action was designed with zero considerations for gas venting. A real "success orientated" program. We don't need to plan for problems because this is a "success orientated" program. Anyone else work on a Polly Anna program that failed? Anyone involved in the invasion of Iraqi?

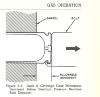

A Mauser M98 barrel seats the case deeper, and uses the inner collar of the receiver to provide even more support.

Read Chinn, you will see stuff like this, explaining action design and cartridge support

The shooting community is nuts in many ways. It has to have the most high performance, highest pressure,

no replacement for displacement, firearm on the market. Because with a lesser performance firearm, you might be robbed lobbing rounds at living creatures at unethical distances.

I am going to say, that pressure is not your friend. The pressure curve has an exponential slope and things go wrong sooner than later with any system operating at high pressures. Remember those driving movies "Speed Kills!". It is all true.

It is better to do the same job with lower pressures, if you are smart enough to figure out how to do that. I could go down a long list of possibilities, but in a large part, the legendary reliability of the M1911 is due to the fact they started off with a relatively low pressure cartridge that did not cause jams once temperatures got a little warmer, and did not require a structure of high quality alloy steels, and the mechanism did not beat itself to death.

We could learn a lot from the Chinese. Their service round operates just above 40,000 psia and is ballistically better at all ranges, in terms of trajectory and KE, than the 5.56. The cartridge has a lot of taper, thick rim, and probably functions with steel case materials. The 5.56 is a jam a matic with steel and not perfectly reliable with brass.

The current 5.56 cartridge is operating at a classified pressure, said to be around 65,000 psia. The proof test used to be 70,000 psia. Not a lot of margin there. Current M4's are going to be cracking bolt lugs even sooner with the latest cartridge, as the action was designed around a 50,000 psia round. And, from what I have heard, military barrels have so much free bore, to reduce pressures, they ought to be considered smooth bore. When you start off with a hot round, and then bump the pressures up, function does not get better, it gets less reliable. The US Military ought to hire some Chinese Engineers on their next rifle, or save a lot of development money and just buy the current Chinese service rifle and cartridge.